Mark Kitto

Forty-six Books

IT NEEDS TO BE SAID: we tend to be too earnest about China—the opacity of its politics, the pseudonymously shielded intimations of sufferings foisted upon its people by a capricious government bent on maintaining one-party rule at all costs, the hagiographies of the system’s entrepreneurial winners.

But perhaps we should qualify “too earnest” with “too sympathetic”—or even “too awed.”

When it comes to China books, the titles alone—or, often more precisely, the subtitles—say it all. Here we have former New Yorker correspondent Peter Hessler in his meditative China opus, Oracle Bones: A Journey through Time in China, and there we have Evan Osnos, another former New Yorker correspondent, with Age of Ambition: Chasing, Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China.

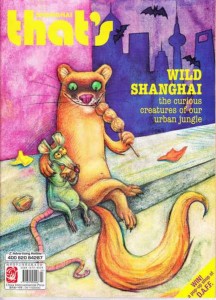

And then Mark Kitto’s That’s China, after 10 years in the publishing wilderness, recently released by Forty-six Books (a media business, Kitto described to me in an email as having “bigger dumplings” than the establishment publishers who had rejected his book for fear of falling afoul of the Chinese authorities). Okay, it has a subtitle, but at least it speaks to more than the abstract: How a Rebel British Publisher Took on the Chinese Propaganda Machine.

Kitto did just that, even if he did not so much “take on the Chinese propaganda machine” than attempt to cooperate with it and then fall out with an arm of it. Nevertheless, his that’s (Time Out-styled) magazines were an immense hit with internationalized Chinese and the gold-rush hordes of foreigners flocking to China in search of unfettered profit and pleasure. In Guangzhou, where it all started, then in Shanghai, and then later in Beijing, Kitto built up a multi-million-dollar media enterprise that spoke to China expatriates in a way that China’s all-controlling—and self-serving—propaganda machine was unable to. Inevitably, this was Kitto’s downfall, but the trajectory of his rise and fall, written in lively, humorous, sometimes acerbic, prose, provides an object lesson in the realities of doing business with China from the ground up.

In short, if we were to make a distinction between That’s China and most of the other China-related tomes jostling for our attention, it might be that the bookshelf consensus is that China is very serious shit—and of course it is, geopolitically and economically. Kitto reminds us that China is that, but above all, it is also absurd and self-protectionist—a point that has been made before in Tim Clissold’s equally humorous Mr. China, published in 2005.

That’s China is the tale of Kitto’s journey from metal trader to self-described “media Moghul.” It starts in 1997, with a magazine called Clueless in Guangzhou, but it is not long before Kitto and the founder of Clueless, Kathleen, a rebel Brooklynite of Chinese heritage with an attitude, a temper (and a fondness for Kitto, if the author is to be believed), set their sights on Shanghai.

‘The city came into view, a brown carpet of the tiled roofs of low-rise old lane houses, the Shanghai nongtangs , built before 1949 and divided by leafy streets. Dirty grey building sites pockmarked the smooth brown surface like cigarette burns on a cheap carpet and in the distance sparkling new glass towers stood up like beacons, beckoning, like the hairs of a Venus fly trap’

Kitto’s admonitory narrative is replete with foreshadowings of this kind, but by his own admission conquering China is an itch he can’t but scratch at, even if it comes at the cost of almost countless compromises with inscrutable, chain-smoking “connections” who promise everything and ultimately deliver a metaphorical kick in the “dumplings.”

The that’s magazines did indeed conquer Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing. But they did so in a country that had flung open its doors to foreign investment as a result of a student—and, later, popular—uprising in 1989 (the Tiananmen protests, or June 4, as they are known) that forced the hand of the Chinese Communist Party. An unspoken deal was struck: follow middle-class aspirations, get rich even, but when it comes to political power, the media, the internal propaganda machine: no concessions.

All the same, China in the 1990s, while it was adjusting to its “reform and open” policy, was a place where every rule appeared to be there to be bent, and when anything seemed possible. Many of us—including Kitto—who were party to this felt freer than we possibly could have at home, wherever that might be. In retrospect, it is easy to see that it was a period of transition. But for privileged foreigners, and some Chinese, it was absurdly “fun.” Everybody was on the make. Everybody was breaking the rules. In fact, breaking the rules was the rule.

To imagine that would continue to be the case was Quixotic, if not slightly mad. In this sense, That’s China is of its time but nevertheless that rarest of things—a racey, amusing, angry read about a country at the crucial juncture it was reinventing itself as the world’s factory and later the engine of global economic growth. As it must, it ends in tears. Step by step, Kitto loses control of what he has built. And behind the humor, the hubris, the adventurism, the adrenaline of Kitto’s tale is a cautionary message.

As Chinese Communist Party patrons and their networks fold under the biggest purge in China since the Mao era, and China shuts its doors on the global internet and Western values, one thing should now be clear: nobody wins a sinecure—or a do-as-you-will publishing license—in a one-party state consumed by patrolling its walls against non-conformist infiltrators.

Kitto did not—that is his story—but he got off lightly. Countless others got off less lightly. They continue not to.

But, as this book makes its case: that’s China.

Harvest Season, a novel by Chris Taylor, is available through Amazon in print and digital formats. In the UK: print, digital.